PILLAR I

Governance and Equality

- Eighty percent of the top 20 countries are full democracies, including Norway, Spain, and the Netherlands.

- In contrast, 85 percent of the bottom 20 countries in the index are ruled by authoritarian regimes, including Kuwait, Sudan and Jordan.

- There are a few countries, however, which are outliers. For instance, Rwanda is ranked 4th in the GEGI for governance and equality but is classified as an authoritarian regime by the Economist Intelligence Unit.

- Forty-seven countries have had a woman serve as the central bank governor or finance minister.

Women’s suffrage has come relatively recently: the average time since women were granted the right to vote is a mere 67 years. Even where women have legally been granted the right to vote, they have encountered religious and cultural obstacles that discourage their participation in governance. As a result, women are still grossly underrepresented in political decision-making.

Gender equality will not be achieved by simply removing barriers to opportunity. We must evolve from an emphasis on equality of opportunity toward ensuring equality of outcome, since economic growth and social progress depends on the active engagement and influence of women in governance.

First, the GEGI analyzes the extent to which a country’s legal framework supports gender equality. For instance, a legal indicator of a country’s commitment to gender equality is its adherence to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Although 188 UN member states have ratified CEDAW, 59 retain reservations that block full implementation of its statuses.

Furthermore, the GEGI examines the proportion of women in key positions in each country. Only 72 countries in the GEGI have had a female president or prime minister for any length of time since 1945.

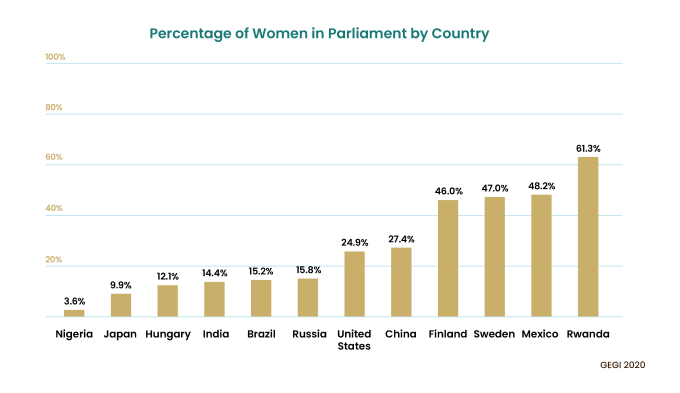

At present, female heads of state or government preside in only 22 countries of the world and only 10 countries have female central bank governors. According to the Inter-Parliamentary Union, only 25 percent of representatives in the combined houses of national parliaments globally were women as of December 2020.

Exclusion and discrimination remain pervasive, and women are still underrepresented at the apex of the judiciary in most countries.

More and more countries are using quotas for elected legislative bodies, with promising results. Where these laws exist, there is more government spending on social services and welfare and lower rates of corruption. Countries with quotas for women in parliament also show a higher degree of women participating in the labor force.

PILLAR II

Education for Equality

- The top 23 nations of the GEGI under this pillar are all democracies, although about a quarter of these are classified as flawed democracies.

- The top 40 countries of the GEGI for this pillar are either high income or upper middle-income countries.

- There are, as usual, exceptions to the rule. Gabon and Nigeria are major oil producers, but rank 155th and 149th respectively on the education pillar of the GEGI.

- The country with the highest mean years of schooling for females is Estonia, or almost 14 years.

Efforts to address gender inequality through legislation, leadership and political reform are insufficient. When women and girls are denied access to education, patriarchy prevails, and human capital is wasted. Inequalities in education artificially reduces the pool of talent from which companies and governments can draw, and thus a direct way to boost economic growth is to expand educational opportunities for girls. With the right tools at their disposal, women and girls have proven themselves to be the source of innovative solutions to pressing global challenges.

Unequal levels of education reduce the quality of human capital on average across a population and can substantially retard economic growth.

The world has made significant strides in female education in the past decades. The World Bank reported in 2018 that girls’ primary, secondary, and tertiary school enrollment worldwide is closely approaching that of boys. While these strides are laudable, such figures mask dire situations in individual countries. The World Bank reports that in many countries, including Angola, Bhutan, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Mali, and Nepal, more than half of all women have not completed even a primary level of education. 500 million women in 2016 were illiterate – more than 60 percent of the total illiterate population.

Many academic studies have shown that large gender gaps in education, particularly in Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East, significantly reduce annual economic growth rates. Devoting more resources to equal education can empower women both in the domestic sphere and in the workforce. Each additional year of education for girls is reflected in delays in the age of marriage and first pregnancies, reduction in sexually transmitted diseases, increased lifetime income, and improved health care within families. It is therefore no surprise that the world’s most competitive countries and economies, including those that produce and embrace new technologies, are marked by the highest opportunities for women’s equality in the classroom.

PILLAR III

Women and Work

- The top 20 countries of the GEGI in women and work are high income, democratic states. The overwhelming majority of them are members of the European Union.

- Currently, 18 countries in the world do not allow women to obtain a job in the same way as a man. These countries are all authoritarian regimes and are mainly in the Middle East, North Africa, or Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Some 70 countries in the world do not allow women to work in the same industries as men. These countries span all regions, income levels, and regime types.

- In Russia, there are over 450 jobs that are off-limits to women, including many highly paid jobs in the energy sector and in the transportation and industrial manufacturing sectors.

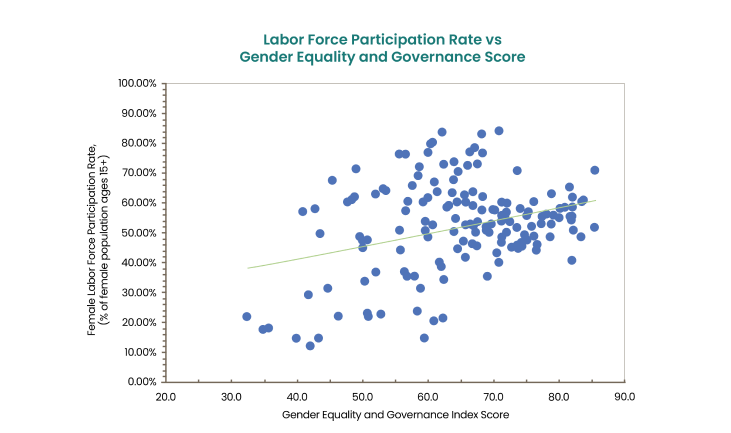

As in education, inequalities in employment are toxic to economic growth because they constrain the labor market, making it difficult for firms and businesses to scale up efficiently. Countries that have integrated women into the workforce more rapidly have improved their international competitiveness.

We observe a political or ideological aspect of discrimination against women contributing to the economy. In authoritarian and hybrid regimes, women face greater restrictions on

working than in full or even flawed

democracies.

The GEGI tracks several variables that influence a woman’s choice to engage in salaried employment. Although female-friendly workplace practices are on the rise, women in most countries must choose between raising children and working for pay. In the absence of paid parental leave, tax-deductible childcare services, and guaranteed non-discrimination during the child-rearing years, these two choices become mutually exclusive. In 50 countries, paid leave of at least 14 weeks is not available to women. Only 43 countries provide for paid parental leave.

Beyond incentives, there are many countries where legal barriers and social norms explicitly restrict women’s participation in the workforce. 100 countries impose restrictions or prohibitions on the kinds of jobs women can hold. The sectors where women make up the vast majority of the workforce, such as care work and the service sector, tend to be lower-paying and with less opportunities for advancement. Even in these women-dominated sectors, men hold the majority of managerial and supervisory roles. Finally, in about half of countries covered in the GEGI, the law does not mandate equal remuneration. As a result, women earn less than men for comparable work, a form of discrimination which greatly contributes to the feminization of poverty.

PILLAR IV

Entrepreneurship and Doing Business

- Nearly 60 percent of women have accounts with a financial institution or with a mobile money service provider, but the range of variation is very large from about 7 percent in Burundi to 99 percent in Denmark

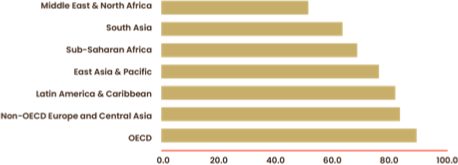

- Authoritarian regimes score lowest in allowing women equal access and opportunities in entrepreneurship. Seventeen of the worst ranking 20 countries globally have this type of regime.

- Countries ranking worst in this pillar span income groups, ranging from low income to high income, which indicates that other factors are at play.

- Other than COVID-related, women face less mobility restrictions in the world today than 10 years ago. Countries with mobility restrictions vary by regime type, region and income level. Two countries share the lowest ranked spot: Iran and Oman.

Women’s lack of access to financial accounts and services is most acute in low income countries, where only 32 percent of women, on average, have a financial account.

Women entrepreneurs have greater difficulty securing credit than men. The International Finance Corporation has found that women entrepreneurs face a global financing deficit of $1.5 trillion. Women’s lack of access to financial accounts and services is most acute in low income countries, where only 32 percent of women, on average, have a financial account. Furthermore, because women tend to earn less and have fewer property rights than men, they have a harder time providing collateral to secure a loan.

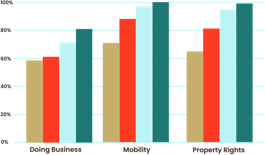

Entrepreneurship and Doing Business Pillar Score

By Regime

By Region

Society has much to gain from closing the gender gap in entrepreneurship. On average, women invest 90 percent of their earnings back into their communities — compared to just 35 percent for men. Economists have identified economic benefits associated with increased earnings for women, including higher savings, more productive investments, and more reliable repayment of credit. Potential strategies to increase women entrepreneurship include creating incentives for investment in women-owned companies, developing mentorship programs to train young women entrepreneurs, and expanding new sources of capital like crowdfunding and microloans.

PILLAR V

Violence Against Women

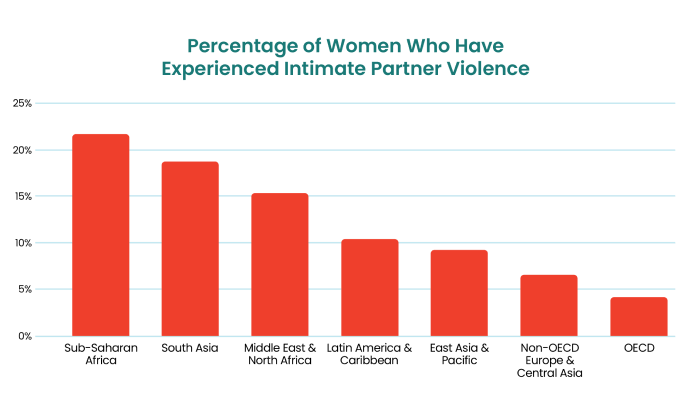

- Of the 20 countries that have the best aggregate score on this pillar of the GEGI, more than half are in Europe. Sub-Saharan Africa scores lowest, followed by the Middle East and North Africa.

- The lifetime risk of maternal death across the world is one in 3,864. However, in countries such as Chad, South Sudan, and Sierra Leone, this risk is closer to 1 in 20.

- Currently, 30 countries do not have domestic violence legislation.

- Globally, on average, 56 percent of women feel safe walking alone at night.

Women are most vulnerable to violence in cultures where long-held customs and fundamental prejudices place the blame for violence on the women themselves. The WHO reports that one-third of all women will experience violence at some point, and one-fourth will experience domestic abuse. Nearly 60 percent of all women killed intentionally in 2017 were murdered by intimate partners or family members. Women and girls make up 72 percent of all sex trafficking victims.

Every full democracy has legislation

protecting women from domestic violence and sexual harassment and around 90 percent of flawed democracies can say the same. By contrast, only 54 percent of authoritarian regimes have domestic violence legislation, and only 65 percent have legislation addressing sexual harassment in employment.

For centuries, guilt and shame have been tools to convince women that they are complicit in the crimes committed against them. As a result, most violence against women goes unacknowledged, unreported, and unaddressed. It is estimated that only one-fourth of physical assaults, one-fifth of all rapes, and one-half of the stalkings that take place in the United States are reported to the police. Fewer than one-third of women experiencing domestic violence globally will ever say anything about it publicly. This makes it particularly difficult to measure with any accuracy or to devise effective solutions.

The GEGI assesses a number of factors in an attempt to capture the full picture of violence against women, both de jure and de facto. These include lifetime risk of maternal death, women’s self-assessments of safety, danger of intimate partner violence, legislation on domestic violence and sexual harassment, and the prevalence of “son preference.”

Conclusion

The Gender Equality and Governance Index provides a data-driven, objective look at the state of gender equality in the world, bringing together some 60 indicators to assess the progress made by countries in narrowing gender disparities. As this exercise is repeated biennially it will also provide a vertical perspective on the progress countries are making with respect to their own past since, in the end, it is not so much the ability to assess the performance made by other countries that provides the real value of indices, but rather the ability to track progress at home, where public and other policies can be formulated in a way that reduces gender inequalities.

The calamities brought about by the COVID pandemic has highlighted women's many vulnerabilities as a result of long-standing discriminations across virtually every country in the world. COVID has been the most destabilizing shock to the global economy at least since the Great Depression but, as we saw in the report, the evidence convincingly shows that its impact on men and women has been asymmetric, with the latter being more adversely affect, whether in respect of the job market, the incidence of violence against them or other metrics captured in the index.

In early 2022 the world faces an uncertain economic and security situation. There is an economic recovery underway, but experts are divided on its inherent strength and sustainability. The picture is made more complicated by the whole series of unresolved global problems which we confront, from climate change and its associated repercussions, to an unsettled security situation in many parts of the world—Ukraine, the South China Sea, the Middle East to name a few—reflecting the unfoldment of potentially destabilizing superpower confrontations. But this is not all. COVID has set back in a major way the progress made over the past 30 years in reducing the incidence of extreme poverty and it has clearly also undermined efforts to narrow income disparities. On all of these fronts women and girls are especially vulnerable and run the risk of bearing a disproportionally large burden of whatever ill-advised decisions may be made on many of these fronts by our still very male-dominated political culture.

More than ever before the world needs the empowerment of women, politically, economically and across every sphere of human endeavor. The costs of her absence from the corridors of power over the past century have been too high and, with the developments of new technologies and their possible misuse, persistent nationalisms which stand increasingly at odds with emerging notions of global citizenship, particularly among the young, and deep-seated inertia and lack of imagination among those currently managing our global commons, we are approaching a time when the integration of women into high-level decision making will not longer be just an issue of fairness and human rights, but an indispensable condition for survival. The stakes are too high and we can no longer wait.