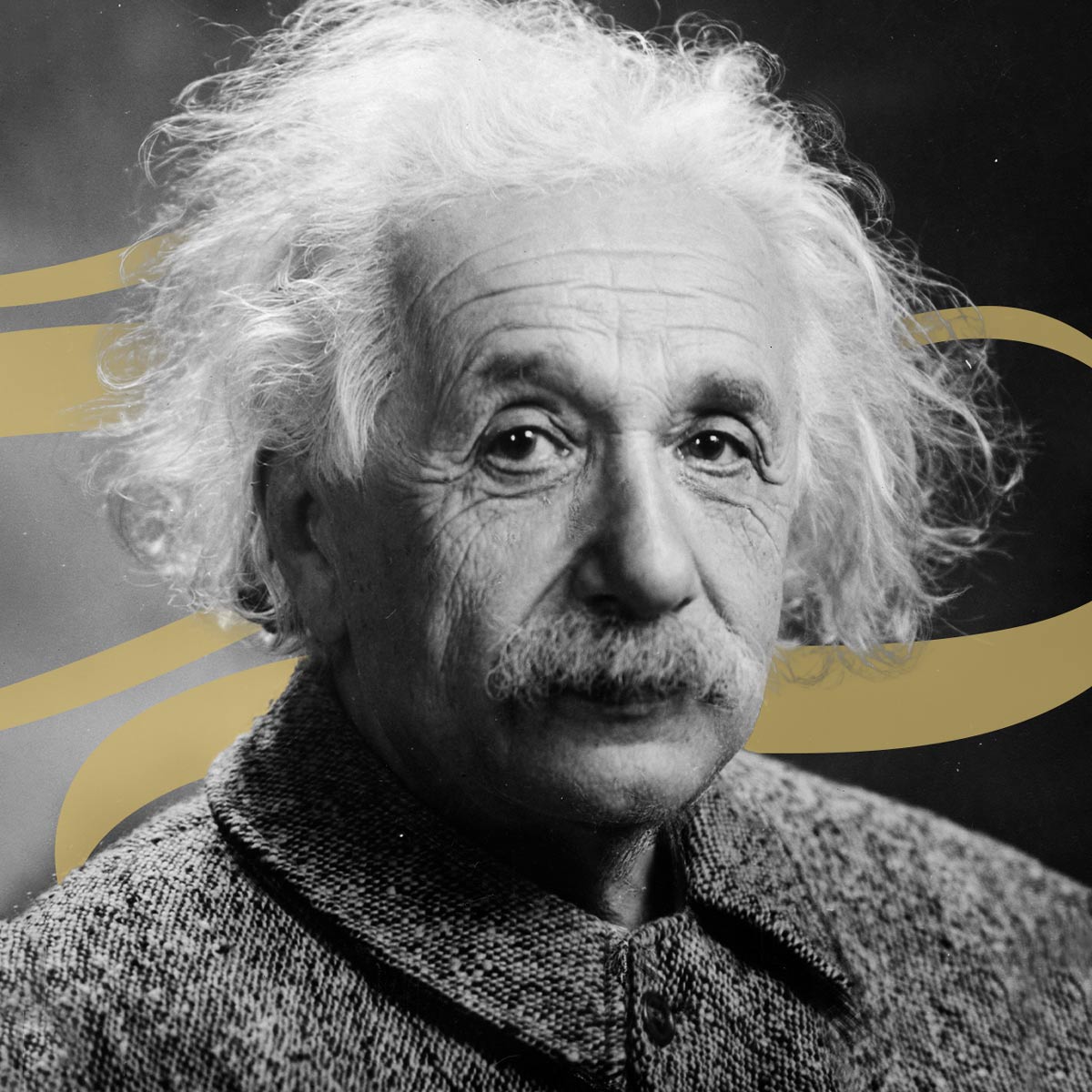

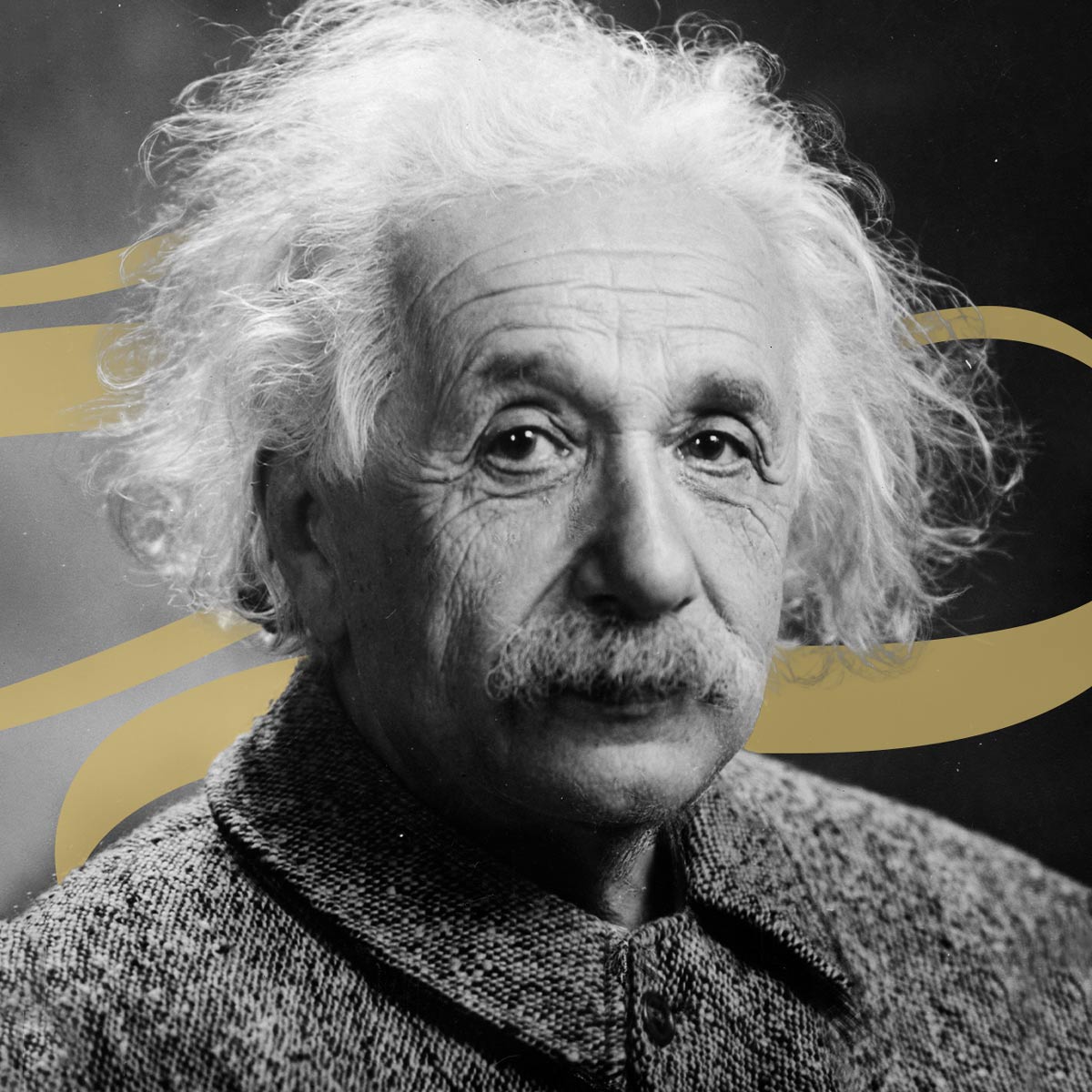

Albert Einstein

Nobel Prize Winner and Hero for World Peace

Nobel Prize Winner and Hero for World Peace

Nobel Prize Winner and Hero for World Peace

Albert Einstein (1879 – 1955), winner of the 1921 Nobel Prize in physics and creator of the theory of relativity, was one of the two pillars of modern physics, best known for his mass–energy equivalence formula E = mc2, dubbed “the world’s most famous equation.”

Perhaps because of his involvement in the development of the atomic bomb, and his horror of it, Einstein was called on to give his opinions on matters unrelated to science. As early as 1914, in response to the Manifesto signed by 93 leading German intellectuals in support of the German war effort, Einstein and three others wrote a counter-manifesto. A passionate commitment to the cause of global peace throughout his life gradually led him to support the creation of a single, unified world government capable of checking the power of nation-states. Seeing himself as a citizen of the world, Einstein wrote in 1947, “I saw how excessive nationalism can spread like a disease, bringing tragedy to millions.” He had a visceral dislike for the deep-seated nationalisms that had caused such grievous damage during the 20th century and once said that nationalism was an “infantile disease,” the “measles of mankind.” It was undesirable and fundamentally a sign of immaturity. To combat this “disease,” Einstein wanted to eliminate nationalistic sentiments—first by erasing the political borders between countries and then by instituting an international government with sovereignty over individual states. During World War I, Einstein supported the formation of the “United States of Europe” and later endorsed the League of Nations and its successor, the United Nations.

But Einstein worried that the United Nations, which answered to the national governments of its member states, did not have enough authority to ensure world peace or prevent future wars. He saw world government as the only way to ensure lasting world peace, which could be guaranteed only when the leaders of individual nations answered to a single, supranational government.

In a 1947 open letter to the General Assembly of the United Nations, he expressed his disappointment that, “since the victory over the Axis powers… no appreciable progress has been made either toward the prevention of war or toward agreement in specific fields such as control of atomic energy and economic cooperation.” As he saw it, the solution required a “modification of the traditional concept of national sovereignty.”

… for as long as atomic energy and armaments are considered a vital part of national security no nation will give more than lip service to international treaties. Security . . . can be reached only when necessary guarantees of law and enforcement obtain everywhere, so that military security is no longer the problem of any single state. There is no compromise possible between preparation for war, on the one hand, and preparation of a world society based on law and order on the other.

Einstein described his proposal more comprehensively in an earlier editorial he wrote in 1945 for the Atlantic Monthly, in which he lays out a scheme to ostensibly protect against global totalitarianism.

Membership in a supranational security system should not, in my opinion, be based on any arbitrary democratic standards. The one requirement from all should be that the representatives to supranational organization—assembly and council—must be elected by the people in each member country through a secret ballot. These representatives must represent the people rather than any government—which would enhance the pacific nature of the organization.

To Einstein’s mind, the greatest obstacle to a global government was not US mistrust, but Russian unwillingness. After making every effort to induce the Soviets to join, he insisted that other nations should band together to form a “partial world Government… comprising at least two-thirds of the major industrial and economic areas of the world.” This body “should make it clear from the beginning that its doors remain wide open to any non-member.”

Einstein corresponded with many people on the issue of one-world government, recommending in one letter that a “permanent world court” be established to “constrain the executive branch of world government from overstepping its mandate which, in the beginning, should be limited to the prevention of war and war-provoking developments.” Concerning the economy, he believed that “the freedom of each country to develop economic, political and cultural institutions of its own choice must be guaranteed at the outset.”

The development of technology and of the implements of war has brought about something akin to a shrinking of our planet. Economic interlinking has made the destinies of nations interdependent to a degree far greater than in previous years. . . . The only hope for protection lies in the securing of peace in a supranational way. A world government must be created which is able to solve conflicts between nations by judicial decision. . . based on a clear cut constitution which is approved by the governments and the nations and which gives it the sole disposition of offensive weapons. A person or a nation can be considered peace loving only if it is ready to cede its military force to the international authorities and to renounce every attempt or even the means of achieving its interests abroad by the use of force.

— Albert Einstein, Out of My Later Years , p. 138.

2020 Global Governance Forum Inc. All Rights Reserved