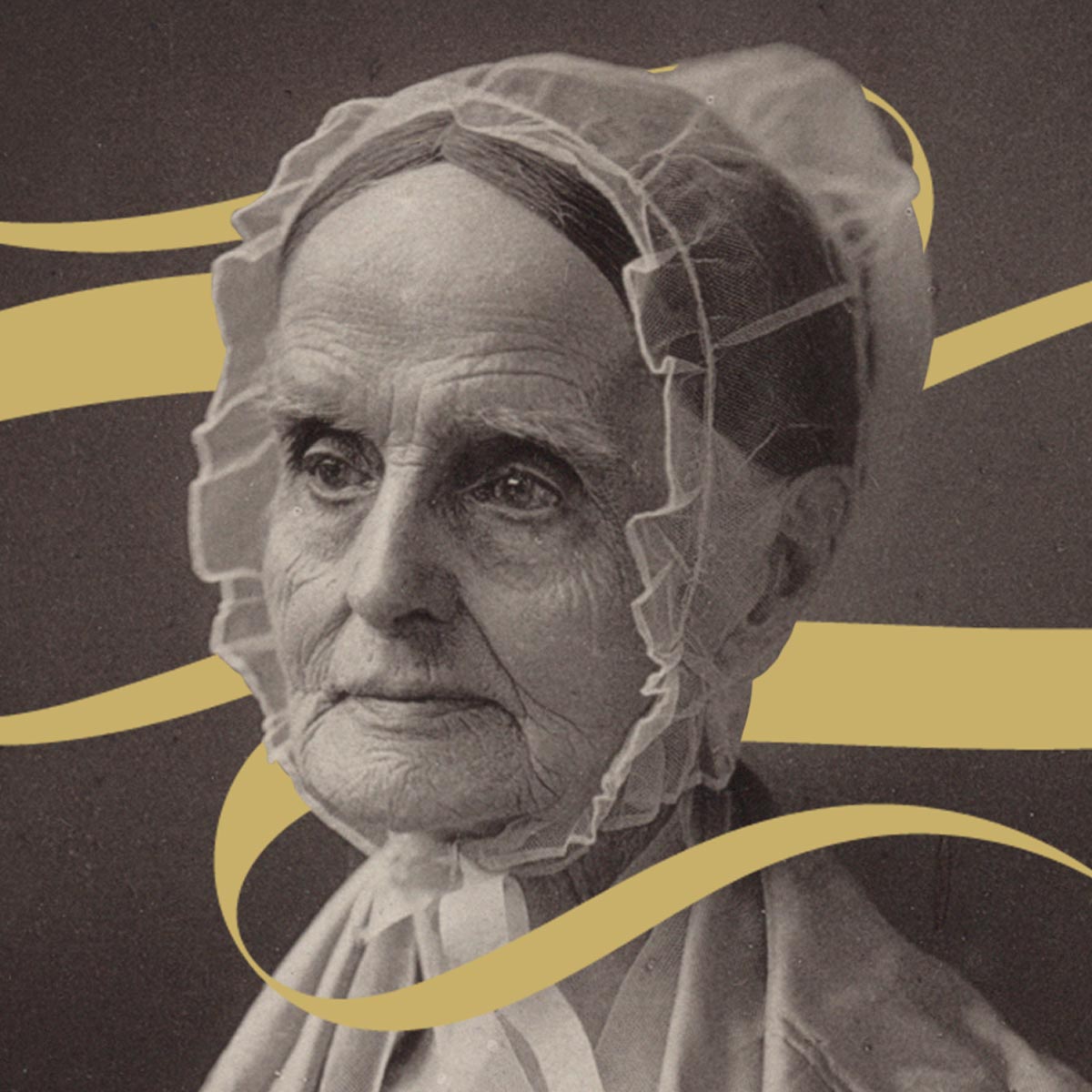

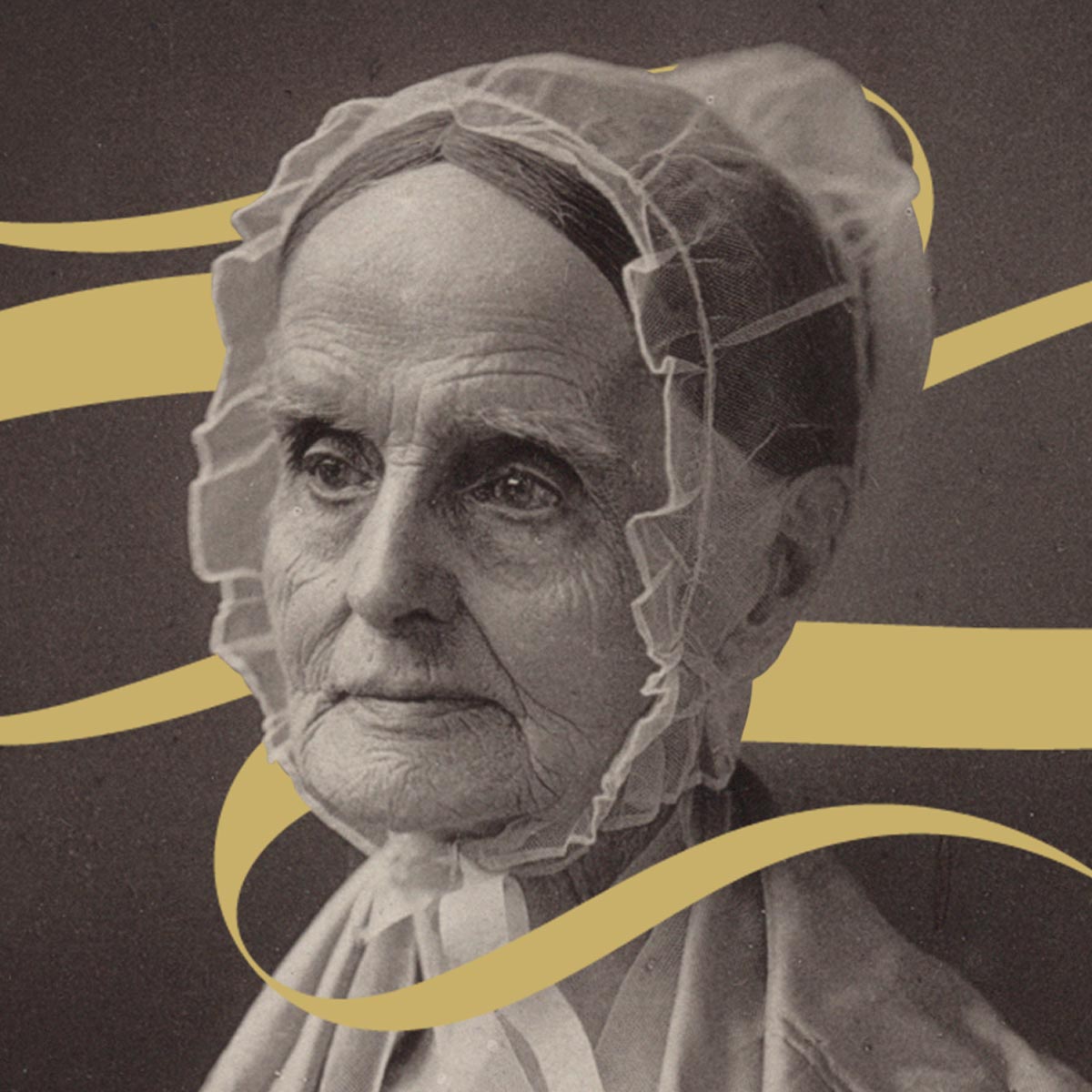

Lucretia Mott

Influential Fighter for Women’s Rights and Abolition

Influential Fighter for Women’s Rights and Abolition

Influential Fighter for Women’s Rights and Abolition

As a fervent anti-slavery activist, Lucretia Coffin Mott attended the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840, only to be told that because she was a woman, she could not be a full participant in the Convention. Raised as a Quaker, armed with the belief that men and women were created equal, she then went on to organize the famous Seneca Falls Convention in New York in 1848 with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who also was barred from participating fully in the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention. The Seneca Falls Convention was the first of its kind and launched the women’s suffrage movement in the United States that led to the eventual passage of the 19th Amendment which secured the right to vote for women. Lucretia Mott spent her life as a strong advocate for both the anti-slavery cause and women’s rights with an extraordinary talent for speaking.

Lucretia Mott was born on Nantucket Island, Massachusetts on January 3rd, 1793 to a Quaker family. She grew up in a community that stressed the equality of all people under God. Her father, Thomas Coffin was a ship captain and kept him away from his family, so he moved them all to Boston to become a merchant when Lucretia was 10 years old. She attended a Quaker boarding school in New York State starting from age 13, and stayed there to work as a teaching assistant where she met her future husband, James Mott. Lucretia Coffin and James Mott were married in 1811 and moved to Philadelphia. The Coffin Family had also moved to Philadelphia and James Mott became Thomas Coffin’s business partner there. When Lucretia’s father died in 1815, Lucretia and James worked to help Lucretia’s mother, Anna Folger, pay her debt and support the family. Lucretia worked as a teacher, James Mott operated a textile business and Lucretia’s mother returned to running a shop.

Lucretia became an active abolitionist speaker and was recognized as exceptionally eloquent. She became a formally recognized Quaker minister in 1821 and used her platform to spread a message of equality. She encouraged her husband to get out of the cotton trade, and they both espoused a boycott and anything made with slave labor, which she encouraged others to join. This work gained her prominence as an abolitionist as she traveled the Northeast speaking about this cause. Her speeches were met with support but also threats and violence for her views and position as a woman speaking on such a radical topic at the time.

Her work as an activist blossomed, and she founded the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1833 with 21 other women in a Philadelphia schoolroom. In 1837, Mott helped organize and attend the First Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in New York City. Lucretia and her husband advocated for abolition as members of William Lloyd Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society in the 1830’s as the organization embraced Mott’s participation. In 1840, Lucretia and James Mott were named delegates from Pennsylvania to the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London. Once they arrived, the Convention had decided that women could not be admitted as full delegates, and Lucretia Mott could only attend as a visitor. It was at this event where she met another visitor and activist, Elizabeth Cady Stanton. As abolitionists excluded from the Convention for nothing but their gender, the two women resolved to call a convention of their own back in the United States to advocate for women’s rights.

The collaboration between Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott lead to the first annual women’s rights convention, the Seneca Falls Convention, held in 1848 in Seneca Falls, New York. Hundreds of people attended the event and the Declaration of Sentiments, a manifesto that described women’s grievances and demands, was presented and called for women to fight for their constitutionally guaranteed right to equality as U.S. citizens with language inspired by the Declaration of Independence. The document states, “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal.” At the Seneca Falls Convention, they passed a list of resolutions, including the ninth resolution, which was the right for all women to vote. This launched the women’s suffrage movement in America that eventually resulted in the passing of the nineteenth amendment.

Continuing her work with the women’s rights movement, she published her speech, “Discourse on Women,” which she gave in 1849 as an appeal for the enfranchisement of women and explained the injustices they suffer. In that speech she declared, “Let women then go on—not asking favors, but claiming as a right the removal of all hindrances to her elevation in the scale of being—let her receive encouragement for the proper cultivation of all her powers, so that she may enter profitably in the active business of life.” Mott became acquainted with Susan B. Anthony and joined her and Stanton in publicly denouncing how the 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution still did not grant the right to vote to women. They then formed the National Woman Suffrage Association which was devoted to fighting for a constitutionally secured right to vote for all women. Mott continued to fight for women’s suffrage throughout her life and attended the thirtieth anniversary of the first Seneca Falls Convention when she was eighty-five.

Lucretia Mott became the president of the American Equal Rights Association and chaired its first annual meeting in 1869. She also was involved in the creation of Swarthmore College, a Quaker institute of higher learning. When the school was initially chartered in 1864, Lucretia and her husband insisted that it be coeducational.

Lucretia Mott did not, however, give up on her anti-slavery activism. She continued to fight for the abolition of slavery, as well as women’s rights until her death. Lucretia and James protested the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and also helped an enslaved person escape bondage. She even met with President John Tyler to advocate for the anti-slavery cause. He was impressed with what she had to say and remarked, “I would like to hand Mr. Calhoun over to you,” referring to the senator and abolition opponent.

Towards the end of her life, Mott spent more time advocating for pacifism and was vice president of the Universal Peace Union. She was also elected president of the Pennsylvania Peace Society in 1870 and served in that role until her death. Lucretia Mott spent her life advocating for equality and peace, concepts that had been ingrained in her since birth through her Quaker tradition. She died in 1880 at age eighty-seven in Chelton Hills, outside Philadelphia. Her activism multiplied the number of participants involved in both the abolitionist and women’s rights movements.

2020 Global Governance Forum Inc. All Rights Reserved