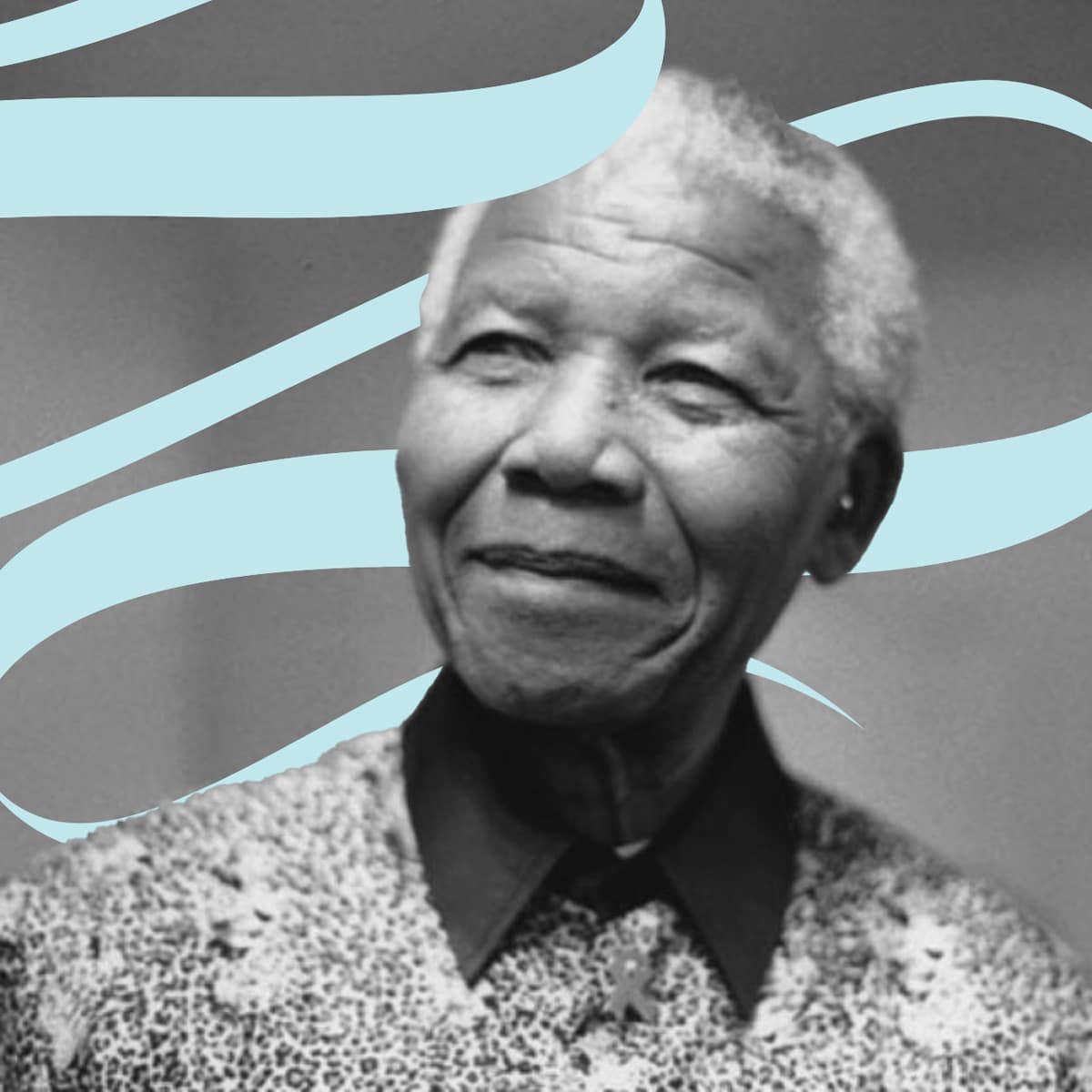

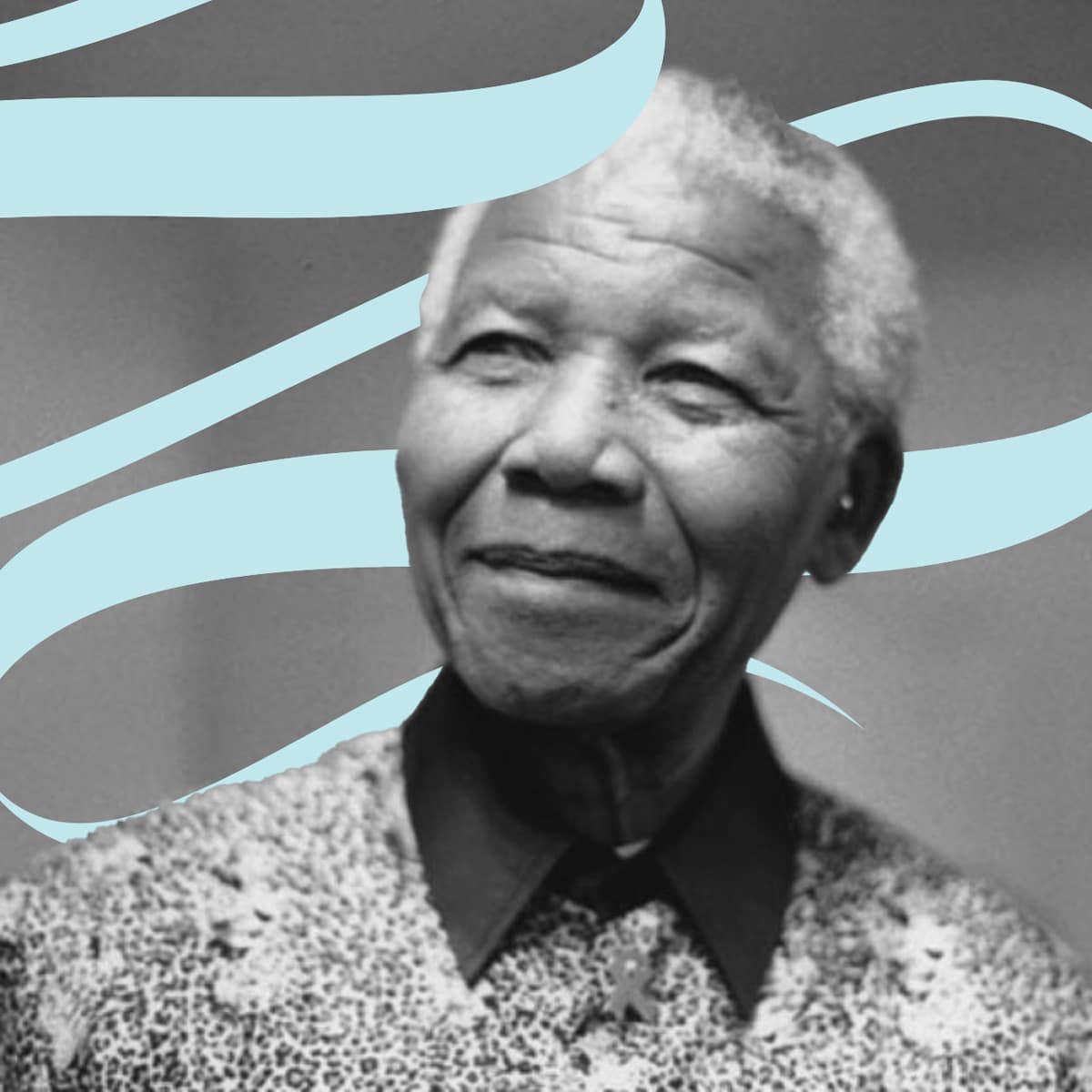

Nelson Mandela

Masterful Negotiator of a Successful Transition to Democracy

Masterful Negotiator of a Successful Transition to Democracy

Masterful Negotiator of a Successful Transition to Democracy

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela served as the first President of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. A revolutionary, political leader, and philanthropist, Mandela carried a self-effacing grace and an ability to appeal to all strata of society. In a 2013 eulogy, then UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon stated “Nelson Mandela was a singular figure on the global stage, a man of quiet dignity and towering achievement, a giant for justice and a down to earth human inspiration.” As the first black head of South Africa – a majority black country – and the first elected in a fully representative democratic election, Mandela’s focus on transforming the country’s legacy of apartheid by dismantling structures of institutionalized racism and fostering racial reconciliation has cemented him as a landmark figure with respect to global governance.

Mandela was born in 1918 into a royal Xhosa family. As a tribal prince educated by white missionaries in his youth and later, at the predominantly white University of Witwatersrand, he developed a familiarity with straddling and balancing conflicting worlds. Mandela grew up steeped in both the traditions of British constitutionalism and of traditional African consensus leadership; together, they would come to influence his political approach later in life. Mandela began his professional life as a lawyer in Johannesburg, where he became involved in anti-colonial and African nationalist politics.

In 1944, Mandela helped found the Youth League of the African National Congress. Although inspired by the teachings of Mahatma Ghandi, Mandela did not view the Indian anti-colonialist’s emphasis on nonviolence as inviolable. As a result, Mandela was repeatedly arrested for acts of sedition. Influenced by Marxism, Mandela joined the South African Communist Party in the late 1950s. Although initially committed to non-violent protest, he co-founded the militant Umkhonto we Sizwe “Spear of the Nation” wing of the African National Congress (ANC) in 1961. In 1962, Mandela was arrested for his role in a purported sabotage campaign. After being sentenced to 5-years imprisonment, he was re-tried in 1963 under charges of sabotage and conspiracy to violently overthrow the government. Mandela was subsequently sentenced to life in prison for conspiring to overthrow the state. Mandela first garnered international attention as a leader of the apartheid opposition after he delivered a four-hour speech from the court at the end of his 1964 trial.

Mandela spent the next 18 years imprisoned on Robben Island. While incarcerated, Mandela spent his days working in a lime quarry and working toward an LLB degree through the University of London at nights. In 1982, Mandela was transferred to Pollsmoor Prison with other senior ANC leaders. In 1988, Mandela was moved to Victor Verster Prison where he enjoyed a better living standard and was able to complete his LLB degree.

Facing domestic and international pressure, then-President F.W. de Klerk released Mandela in 1990. Together, Mandela and de Klerk led efforts to negotiate an end to apartheid, which led to the April 1994 multiracial general election in which Mandela led the ANC to victory and became president. As many feared racial divisions in South Africa could spiral into civil war, Mandela played a crucial part in keeping political negotiations on track. While the transition did not occur entirely without bloodshed, it would have been much worse without Mandela’s skillful statesmanship. Mandela was able to keep the tense negotiations from slipping into armed conflict, while also keeping stakeholders engaged when they otherwise may have been tempted to walk away. It has been said that, during this period, Mandela carried the respect of a head of state even though he had yet to be elected.

Mandela was the President of the ANC from 1991 to 1997. He became President of the Republic of South Africa in 1994, leading a coalition government toward instituting a new constitution. Mandela was thus a central figure in the creation of South Africa’s 1996 Democratic Constitution. The document is the jewel of the country’s post-apartheid democratic order. It is notably aware of the context from which it emerged, relying not on a whitewashed past but on addressing its reason for being; its opening passage states “We, the people of South Africa, recognize the injustices of our past.” Emphasizing the rights of the individual over those of the state, it proceeds to enumerate 32 different articles relating to the fundamental human rights of individuals before outlining the structure of the republic’s government.

The constitution is progressive in its protections of fair labor practices, reproductive health care services, and environmental stewardship. Reflecting on the dehumanizations of the country’s past, the constitution specifically enumerates the right of each individual to a name and nationality from birth and prohibits the use of child soldiers. Moreover, Mandela created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1995 to investigate the country’s history of human rights abuses.

Further underscoring Mandela’s commitment to racial reconciliation was his vision for the South African national anthem. It combines the discordant tunes of “Nkosi Sikelel iAfrika,” a black protest anthem during apartheid, and “Die Stem,” a white celebration of the European conquest of the region. From the two songs deeply rooted in the conflicting identities within the country, Mandela forged a powerful message of national harmony. National unity relied on Mandela convincing the white population of South Africa that they would not be treated as inferiors by the black government. White officials were allowed to keep their positions within the government, effectively giving Mandela a turnkey government when he assumed office.

Mandela inspired the nation to forgive, but never to forget. While frequently described as the “Father of the Nation,” Mandela was not an uncontroversial figure. While conservative critics denounced him as a communist and terrorist, the far-left saw him as being too eager to negotiate and reconcile with former proponents of apartheid.

While the rule of law and preservation of order had served to institutionalize racism under apartheid, Mandela remained committed to repurposing these central pillars of the state for good. Under Mandela, law and order regained their repute and continue to underpin the democratic functioning of the Republic of South Africa. Central to Mandela’s vision for a new South Africa was the idea that “a nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens, but its lowest ones.” Social equity, poverty alleviation, and true democracy were all critical to his platform and mission. Initiatives to these ends included land reform, poverty reduction efforts, and the expansion of healthcare services.

Mandela’s success was, in part, a product of the respect and trust he showed to those who opposed him. He also made it clear that he was committed to a set of values from which he would never be persuaded to depart. Similar to figures such as Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and George Washington, Mandela uniquely transitioned from a successful liberation figure to a successful politician. The requirements of personal loyalty and secrecy that make successful liberators are opposed to the more pragmatic demands of governance. Mandela successfully made the transition from tyranny to democracy through persuasion rather than repression.

Mandela declined a second presidential term and was succeeded by his deputy, Thabo Mbeki. Following his departure from politics, Mandela remained engaged in efforts to combat poverty and HIV/AIDS through his foundation. Mandela acted on the international stage as well, serving as a mediator in the Pan Am Flight 103 bombing trial in 2000 and as Secretary-General of the Non-Aligned Movement from 1998 to 1999.

Mandela received more than 250 honors during his life and posthumously, including the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993 (which he shared with de Klerk). Mandela died in 2015 after suffering from a prolonged respiratory infection.

2020 Global Governance Forum Inc. All Rights Reserved