The United Nations must reform to better represent the interests of the Global South

by Klaus Kotzé

January 6, 2024

by Klaus Kotzé

January 6, 2024

The term ‘Global South’ has its proponents and detractors, but largely represents the interests of developing states in the world’s southern hemisphere. Today, the increasing bulk of the world’s population resides here and the majority of United Nations member states are in this part of the globe. As a political term, the Global South has come to signify those states that hold a marginal, but not inferior, position in global relations. Despite being a very diverse arrangement of states, their leaders typically view the current world order as one dominated by states in the northern hemisphere, and the United States in particular. Rhetoric out of the Global South often portrays this order as unjust, unpeaceful, undemocratic, and unfriendly to its interests.

Global South states contribute 80% of global growth, and are significant players on the world stage…

Amitabh Kant, India’s Sherpa to the G20

According to Amitabh Kant, India’s Sherpa to the G20, Global South states contribute 80% of global growth, and are significant players on the world stage. Today, they serve as the nodes of global expansion and development and drive economic and democratic growth. These roles will only expand. They are also aspirational and generally want to correct the imbalance in global political power. As such, new groupings of states have emerged, such as the Group of 77, the Non-Aligned Movement and, most recently, BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). Wary of (neo-) imperialism and intervention, these states have been closely connected to the decolonization movement and continue to advance global emancipation. States in the Global South advocate for sovereign states to pursue independent foreign policies and national interests, and want international platforms and organisations, such as the United Nations, to provide resources to pursue those interests.

But the future legitimacy of this body [the United Nations] rests on better accommodating the needs of states in the Global South.

States in the Global South differ in size, structure and access to resources and their policies are not monolithic. Different states have their own agency to assert their own policies through their own approaches. Nonetheless, their vision is for a truly multilateral system that comprises a plethora of members. This bottom-up or many-to-one approach – vs. the one-size-fits-all model – seeks a world order where everyone is better off. As such, they seek corrective measures, such as support and concessions from financial institutions and international organisations. Greater parity between states would boost trade, security, and development for all.

The message of the Global South, as expressed via BRICS or the G77, has largely been committed to the United Nations as the only global arrangement able to pursue these ends. But the future legitimacy of this body rests on better accommodating the needs of states in the Global South. Global governance reform has also been a priority for many of these states, since at least the 1960s.

Reform to ensure greater representation and legitimacy offers the best chance to cooperatively address global concerns and to ensure that the United Nations executes its core purpose of improving the lives of the poor, supporting sustainable development, maintaining international peace and security, and protecting human rights. Reform initiatives that do not address the concerns of the majority of the world’s population – and that, therefore, do not address the inequity between the northern and southern hemispheres – would be inadequate.

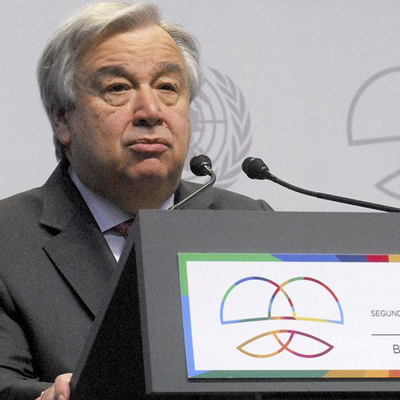

Hence, it is encouraging to see that the United Nations has commenced a new reform programme. In its declaration on the commemoration of its 75th anniversary in 2020, it recognised that “the world of today is very different from what it was when the United Nations was created 75 years ago.” It commits to reform, so as to “ensure a more agile, effective and accountable organization that can deliver better in the field and adapt to global challenges.” Central to Secretary General António Guterres’ mission is improving focus and efficiency; bringing decision-making closer to the people; empowering managers; and restructuring budgetary procedures. The reform process is thus both ideational (orientation) and structural (operations and management).

At the turn of the 21st century, at the Millennium Summit, the UN decided to go beyond traditional peace, security, and humanitarian concerns. Rather, it became an instigator of global norms and ‘good governance’ and offered more visionary, ideational leadership to improve living standards for much more of the world’s population. Programmes such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) and subsequent Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) collectively provided concrete direction guided by principles and values. These areas of focus were the result of extensive debate by the member states.

While these were welcome developments, states in the Global South would like to see more member states in the hemisphere asserting their own meaning and culture within the broader context of multilateral cooperation. Recent reform initiatives, however, are not moving in this direction and are concerning. Namely, diverse stakeholders are being accommodated and listened to without any formal or prescribed partnerships. The paper from which this summary stems assessed recent United Nations documents, including Our Common Agenda in 2021. The assessment suggests a broadened perception of multilateralism that expands upon existing meanings, but also opens space for confusion. Among others, it defers action on current crises and moves responsibility away from the state as the legitimate agent and to unregulated stakeholders, including non-governmental foundations and institutes.

States from the Global South have, through platforms such as the G77, also expressed concern over the arbitrary influence of unaccountable, non-state actors such as foundations and corporations.

As such, current reform proposals may not fully accommodate the interests of the states in the Global South. The latter would like to see specific, enforceable commitments that respect national autonomy and are enacted through state-led partnerships rather than generalised commitments that ignore state-to-state responsibilities and leave delivery of outcomes to a future time. This approach negates the urgent challenges the world currently faces and defers responsibility.

States from the Global South have, through platforms such as the G77, also expressed concern over the arbitrary influence of unaccountable, non-state actors such as foundations and corporations. A new type of universality is introduced, a multilateralism comprising multiple stakeholders, many of whom serve business or other partial interests. Unless the increased role of non-state actors is checked, their influence will be uncontrolled vis-à-vis that of states.

If the United Nations Secretariat continues to turn away from state-centred intergovernmentalism, there may be a further backlash. It is from the relationship-centred, intergovernmental arrangement of member states that the United Nations receives its authority and legitimacy. While states are the occupying agents of territory with a circumscribed authority, they must also ensure that they deliver on their responsibilities and create frameworks that harness the potential of other actors. It’s a fine balance, but one that merits far more consultation.

This article is drawn from the paper: ‘Assessing the official perspective of and approach to United Nations reform’. The paper was recently delivered to the Global South Perspectives Network on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly meeting in New York, September 2023.

Written by Klaus Kotzé

2020 Global Governance Forum Inc. All Rights Reserved