Without Reforms, the Mideast Risks Revolution

by Augusto Lopez-Claros and Danielle Pletka

April 8, 2005

Originally Published in International Herald Tribune , 8 April 2005

Originally Published in International Herald Tribune , 8 April 2005

by Augusto Lopez-Claros and Danielle Pletka

April 8, 2005

Originally Published in International Herald Tribune , 8 April 2005

Originally Published in International Herald Tribune , 8 April 2005

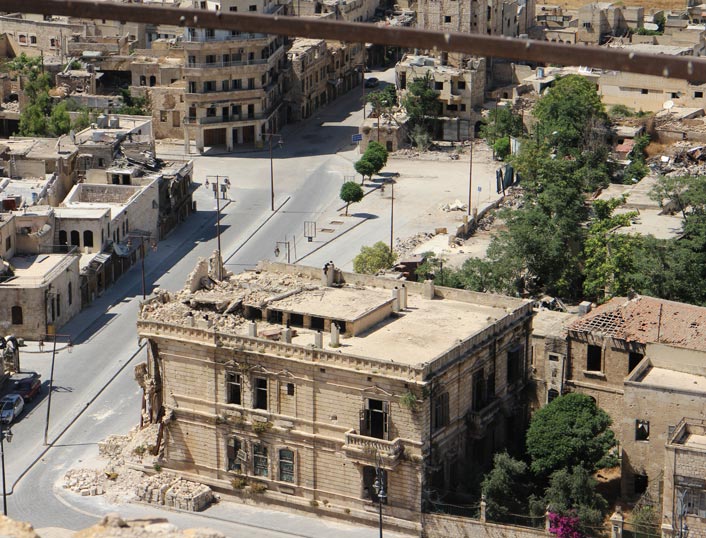

Few doubt that the status quo in the Arab world is unsustainable. The question rather is: if this region is to look substantially different in 2020, where will the promised liberalization come from and how much time is there before the economic challenges confronting Arab governments transform themselves into political crises?

In Libya, over 60 percent of the country is under 15, with unemployment close to 30 percent. In Saudi Arabia, 38 percent are under 15, with 25 percent unemployed. The ILO tells us this is the regional norm: the highest population growth rates in the world, home to more than one quarter of the earth’s total unemployed young people between 15 and 24.

If several million youths are entering the job market each year, where will the tens of millions of jobs come from, in the next 15 years, to satisfy the legitimate needs of these young people? And that, only to keep unemployment rates—also the highest in the world—at current levels. The enormity of the task of employing these teeming Arab millions is not only hard to imagine in current circumstances, but impossible without a major rethink of the current economic “model”.

The statistics paint a sobering picture of decline. In many Arab countries, per capita income has plummeted. The current upswing in crude prices is unlikely to provide much solace, as many countries in the region are already unduly dependant— for exports, for budget revenues—on the energy sector. The singular lack of diversity in earnings leaves them prey to the vagaries of international oil prices. Intra-Arab trade in non-petroleum goods is miniscule, leading to the cliché that nonoil exports from the entire Middle East and North Africa equal the annual exports of Finland. Where will the jobs of the elected body, when television and newspapers cannot step across the political line to report freely. There are few places in the Middle East or North Africa where it pays to be a critic. Indeed, state ownership, political domination and protecting the privileged minority’s access to wealth do not jive with talk of reform.

The development mantra contends that change, if it is to occur, must come from within. But what is the likelihood of organic, home grown change in the Arab world, of having politicians who can be removed from office if they do not perform—better still, who are honest? Do we have the luxury of waiting 50 years for enlightened Arab leaders to emerge, who are strongly committed not just to staying in office, but to improving the public good? Is there a genuine impetus from the grass roots, from the 300 million people of the Arab world?

In a group of countries labeled by the United Nations as among the least free in the world, without a free press or functionning civil society organizations, it is no easy task to describe the will of the people. Young men are especially outspoken, complaining about their dim prospects, and their governments’ failure to provide for their future. Add to that the common perceptions—largely accurate and backed up by United Nations surveys and the work of Transparency International― about institutionalized corruption in the Arab world, and it is easy to see why disillusionment with Arab leaders is common among the Arab masses.

When the leadership of the Arab world has been allowed to define reform, it has become an odd creature. Tireless efforts go to painting enthusiasm for political and economic liberalization as a sinister plot for Western domination, as if such concepts as individual liberty, free markets, or the rule of law were constructs alien and meaningless to the vast mass, however embraced by a tiny, rebellious Arab elite. One cannot swallow such denials, without imagining an entire population devoid of the normal expectations of future come from? What will these masses of unemployed young people do?

In failing to appropriately plan for the future, Arab regimes are risking brewing their own explosive mix. Despite the obvious swell of socio-economic pressures, sustained commitment to economic and political reform has not matched the magnitude of the challenges ahead. In Kuwait, Qatar and the Gulf neighborhood, principles of economic diversity and privatization have started to take root. Tunisia has privatized well over one hundred state owned industries and Morocco has run a close second. Through a process of friendly extortion, western countries have succeeded in linking a portion of Egypt’s annual assistance to economic reform. In the early 1990s, it appeared that Egypt had seen the light, and price controls were eased, agricultural regulations relaxed and trade and investment laws liberalized―up to a point. Syria talked a good game at the beginning of the 1990s. When foreign exchange rates were liberalized, Syria’s well-connected business community rejoiced, encouraging expatriates to come home and invest their earnings. Morocco under King Mohammed VI held free and fair elections, in a visible departure with the past. Bahrain broke the mold, and began to move on privatization and institutional reform. There have been some promising steps in Yemen.

But even these limited reforms do not measure up compare with western democracies, and in recent years, have ground to a halt. The major privatizations necessary to get government out of the business of business have been missing. Kuwait’s public sector still employs 94 percent of the national labor force. Free elections are only half the story, when parties are not free to form, when a king’s appointed parliament has equal powers to government: security, education, social services, accountability, moral scruple, concern for justice. One has to conceive of a world against nature, where all personal ambition—based on merit and hard work, rather than government connections or bribery—the desire for the freedom to express oneself, to cavil at unrepaired streets, at isolation from the world of modern technology, at the absence of meaningful, forward-looking education, at cruel and senseless restrictions against women, at the ease with which regimes construe any criticism as a threat—in short, where all human striving has somehow been thrown overboard.

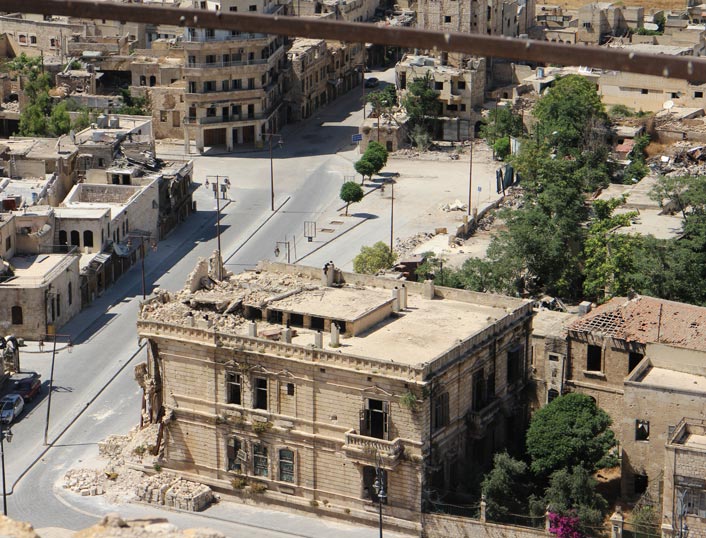

On the contrary, there exist deep wellsprings of anger, frustration and bitterness in the Arab world. In these one-party states and stifling monarchies, there is a desperate search for a means of protest. The many gods that failed throughout this decades-long search have been cast aside: Nasserism is dead, as are illusions of Arab union. Ba’athism is finished in Iraq, and bankrupt in Syria. Even the far more soothing nanny statism of the Gulf is fading as oil treasures dwindle. Many have come to the painful realization that they will offer their children far less than they themselves received.

For any intelligent observer or insider, it is increasingly obvious that the false populism and religious fanaticism of Islamic extremism offer no real political, economic or social model capable of satisfying the real world requirements of a growing Arab world. Immediate political reform is what is needed, for where genuine political parties and grassroots movements flourish, there will be limited enthusiasm for the nihilism of a bin Laden. If they are not freed to find those solutions for themselves through free thought, private enterprise, political ferment— including the right to demand accountability and change government—then the current leadership of the region, sooner or later, will face revolution, doubtless the wrong kind.

Written by Augusto Lopez-Claros and Danielle Pletka

2020 Global Governance Forum Inc. All Rights Reserved